“We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the earth.”

This is the astonishing observation of William Anders who took the iconic “Earthrise” photo from Apollo 8. Before this mission, no one had seen the Earth suspended in space. That revelation has profoundly transformed countless astronauts. It is reported that Alan Shepherd cried, not when he first set foot on the moon, but when he looked back at his home planet.

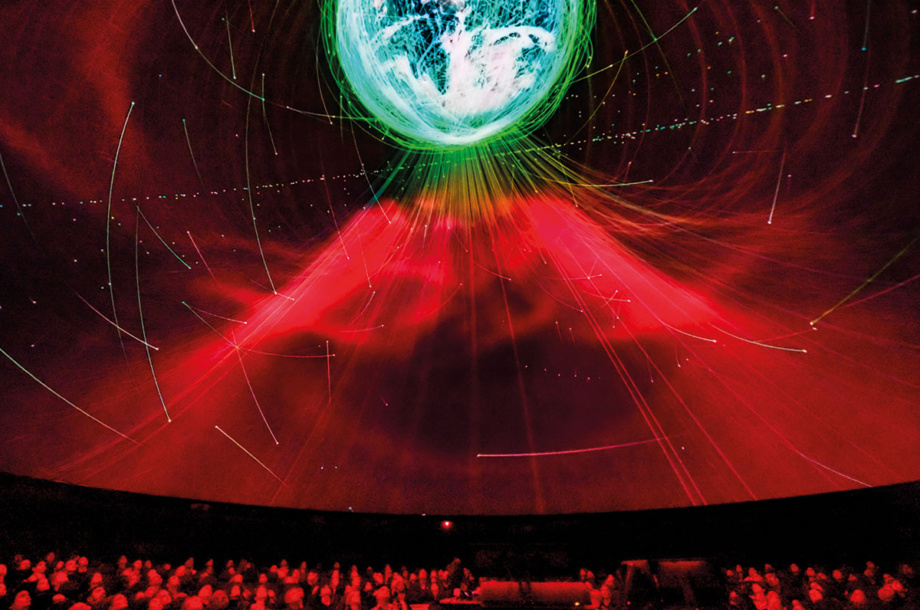

Last Thursday, my son and I hurtled through our solar system at the Hayden Planetarium here in New York City. While not in space, we experienced a fraction of what has come to be called The Overview Effect, the experience of seeing Earth more than 20,000 miles out. The Overview Effect is a cognitive shift in awareness, seeing firsthand the reality of Earth in space – a tiny, fragile ball of life, hanging in the void, shielded and nourished by a paper-thin atmosphere.

We learned about how and why every other planet is inhospitable to life, reminding us just how unbelievable it is that advanced and complex life on earth not only came to exist, but flourish! Every other planet, a barren wasteland, ours a brilliant and beautiful jewel. How did we get so lucky to call this beautiful place home?

After the show we wandered the halls of the American Museum of Natural History. We stood, completely dwarfed, before a cross-section of a 1,400 year-old Sequoia tree, felled in 1891 (before it was illegal to cut them down.)

Theodore Roosevelt, a great lover of American forests, wrote: “A grove of giant redwood or sequoias should be kept just as we keep a great and beautiful cathedral.” The display noted that the bark of Sequoias is flame-resistant. But, of course, in the face of climate change, this is no longer true. Wildfires have become such incredible infernos they are, in fact, killing these magnificent giants.

We then went to the Hall of Biodiversity, a veritable sea of plants and animals lining the walls, a potent reminder that we are not the only living things to call this earth home. After that, onto the Hall of Gems and Minerals, more than 5,000 specimens from 98 countries in every texture and color, imaginable and unimaginable.

As much as I loved sharing the experience of such wonder with my son, I also felt a certain pang: “All of this is threatened!” But it made me more determined to lead a life that preserves and protects our home, one that exists against all odds and provides us with more than we could ever hope to give it in return. If I wanted my son to show all these wonders to his children, I would have to keep making important choices. That’s the aim of Planetarian Life.